One of the most iconic photographs from the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, TN features two rows of women sitting in front of imposingly large machines covered with meters and dials. Taken by the legendary photographer Ed Westcott, this picture captures a typical day for the “Calutron Girls,” the women charged with the task of monitoring and maintaining the mass spectrometers at the Y-12 uranium enrichment plant.

Although they didn’t know it at the time, these young women were forever altering the course of human history by supporting the development of the world’s first atomic weapons. Read on to learn how a group of recent high school graduates became important contributors to the Manhattan Project.

Women Move to Oak Ridge in Droves

shift change at y-12 8-11-1945 937-1

During World War II, thousands of women moved to the newly established city of Oak Ridge in search of a better life. With many young men serving overseas, there was a demand for a new female labor force. Women were drawn to jobs at Clinton Engineer Works (a front for the Manhattan Project) with promises of good pay and affordable lodging. A former calutron girl, Gladys Owens, recalled that the rent at her dormitory was $10 per month.

While many of the women who moved to Oak Ridge were from nearby towns in Tennessee, workers came from around the South and even from towns in the Midwest and cities in the Northeast. By 1945, 75,000 people were living and working in the Secret City.

Becoming “Calutron Girls”

The Y-12 Plant at Clinton Engineer Works was home to a number of calutrons, machines that use an electromagnetic process to separate uranium isotopes (an essential step for building atomic bombs). When they were developed at the University of California, Berkeley, the calutrons were only operated by PHDs. At Clinton Engineer Works, however, the calutrons were operated by young women, most of whom were recent high school graduates.

Seated at the calutrons’ control panels, these women were responsible for monitoring the devices’ meters and adjusting the dials as needed. The Calutron Girls were given absolutely no information about the significance of what they were doing; the training they received pertained strictly to the task at hand.

When women were hired to operate the calutrons, some of the physicists at Y-12 didn’t think they were up to the job. However, the Y-12 supervisors ultimately found that the young women were better at monitoring the calutrons than the highly educated men who used to operate the machines. If something went wrong with the calutron, male scientists would try to figure out the cause of the problem, while women saved time by simply alerting a supervisor. Additionally, scientists were guilty of fiddling with the dials too much, while women only adjusted them when necessary.

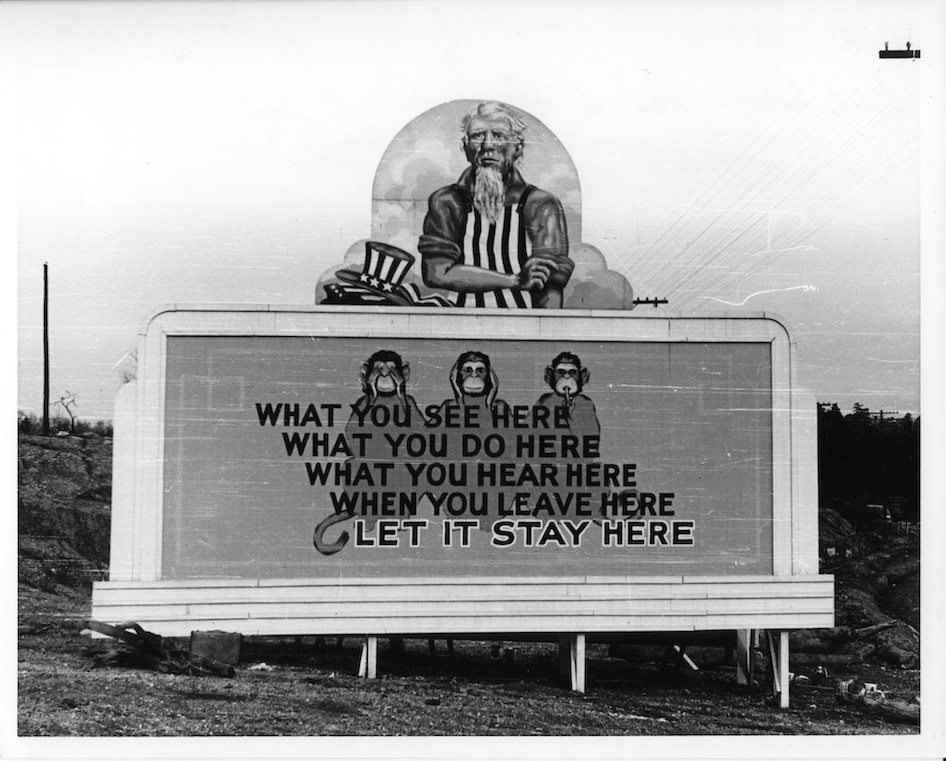

Taking Secrecy Seriously

Oak Ridge wasn’t called the “Secret City” for nothing; the safeguarding of sensitive information was a top priority. Former Calutron Girl Gladys Owens recalled that her manager at the Y-12 Plant told the team, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!”

Like all of the other employees at Clinton Engineer Works, the Calutron Girls were forbidden from discussing their work with anyone. Those who asked too many questions had a habit of disappearing. When one young woman did not return to Gladys Owens’ dormitory, her neighbors were told that she had “died from drinking some poison moonshine.”

New Opportunities and Old Obstacles

For many young women, working at Clinton Engineer Works was the first time they had left their families and rural lifestyle. Although it wasn’t a big city like Nashville or Memphis, Oak Ridge had movie theaters, roller rinks, recreation centers, and other places for young people to socialize and have fun. Living in dormitories and earning money was an exciting and empowering experience for many of the women living in Oak Ridge.

While life in Oak Ridge presented many new opportunities for women, it was still governed by the restrictive social mores of the day. Very few women were promoted to positions of authority at work. Also, Clinton Engineer Works’ housing policies mandated that the dormitories be segregated by race and gender.

After the end of the war, calutron activity scaled down at Y-12 and the Calutron Girls moved on. Even after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many of the former Calutron Girls did not know how much they had contributed to the war effort. Gladys Owens, who is seated in the foreground of Ed Westcott’s famous photo, did not realize the significance of her work until she came across the picture during a public tour of the Y-12 Plant fifty years after the war ended!

Learn More About Oak Ridge’s History

Want to read more about the Manhattan Project? Visit our History page to learn all about Oak Ridge’s fascinating past!

This blog draws on the article “The Calutron Girls” by Oak Ridge historian D. Ray Smith